- Home

- Edward Lee

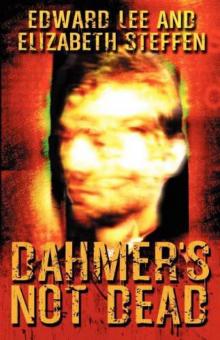

Dahmer's Not Dead Page 3

Dahmer's Not Dead Read online

Page 3

“No, ma’am.” The corporal stolidly pointed again toward the ravine. “Sergeant Farrell, right over there.”

Helen turned without further word. Farrell was down on one knee beside the CES van, his forehead in his hand.

She could see that he’d vomited. “Are you all right, Sergeant?”

Farrell looked up, blinked hard. “I—”

“Get up, straighten yourself out,” Helen ordered. There was no other demeanor she could maintain. If she didn’t keep up the bad-ass routine, these kids would never take her seriously.

“This is a real bad 64, Captain.”

“I know it’s a bad 64, Sergeant, I know it’s a baby, but we’re all out here to do a job. Were supposed to be in charge, and I can’t have my officers keeling over on the scene like a bunch of greenhorns straight out of cadet school. You’re a Wisconsin State Trooper, start acting like it. If you can’t do your job, say so, and I’ll have you relieved.”

Farrell, trim and large, rose to his feet. He gulped hard. His embarrassment was plain. “What should I do, ma’am?”

He probably has kids himself, she suspected. She knew the look. He’s probably got a little baby… “Just hold tight and keep the scene secure, that’s all I need you to do.”

The moon shone like a pallid face over the dead cornfield. Helen strode off the hardtop, then marched awkwardly into the ravine. She felt a bit silly; this was a rural murder site and here she was wearing Nine West pumps, a $400 Burberry topcoat, and a merle sheath dress from Carole Little. Don’t trip and fall in the ravine, she stupidly warned herself. Those county dopes would be laughing it up for a week.

Helen could never discern why, but she knew that Jan Beck, the TSD field chief, didn’t like her. She refused, for instance, to call Helen by her first name, which was perfectly appropriate for two female employees of the same pay grade. But then it occurred to her more clearly that nobody on the department liked her save for Olsher and the rest of the brass. Helen didn’t even care any more.

“Hi, Jan,” Helen said to the slim, crimson-garbed figure. Jan Beck’s silhouette seemed to disgorge itself from the lights. She had thick glasses and frizzy black hair like a witch’s.

“Captain Closs.”

“How’s it look?”

The phantom techs roved behind her, wielding their portable UVs. “White/male infant, about a year old. Full body contusions, looks like an impact death.”

“Beaten, you mean?”

“No, I don’t think so. Looks to me like the baby was thrown from a moving vehicle.”

Helen’s eyes indicated the latent techs. “Then what are they doing with the UVs?”

“Checking the skin before we move the body to the shop.”

“Any signs of violence?”

Beck frowned. “Aside from being thrown out of a moving vehicle?”

“No signs of battery, no signs of sexual abuse? Come on, Jan, you know what I mean.”

“I can’t really make a positive determination on that until I get the baby to the lab at St. John’s.”

Helen knew what Beck was driving at. But I have rules, and I’ve got to go by them. “Jan, there’s no way I can give this 64 a VCU status—”

“Oh, come on, Captain!” Beck snapped. “It’s a one-year-old baby, for Christ’s sake! Some Dane County redneck threw a naked baby from a moving vehicle!”

“I realize that,” Helen replied without any change in her tone. “But you know the rules. I can’t authorize VCU status unless it’s a repeat m.o. in multiple jurisdictions, a multiple homicide, sex related, or suspected of involving the murder of a police officer.” Helen bit her lower lip. “If I write this as a VCU priority, Olsher will have the paperwork torn up before he has his first morning coffee. We can’t carry everyone, Jan. Dane County has a department, they have people. They’re gonna have to investigate this themselves. I don’t like it any more than you do, and if I caught the guy that did this, I’d park my front tires on his head. But you know the rules.”

Beck avoided a deleterious facial affect, which she was very good at. “So what do I do? Can I at least transport the baby’s body to the state morgue?”

“No, Jan,” Helen ordered. “Pack up your stuff and your team. Dane County’s going to have to take the corpse to their own hospital and have it autopsied by their own medical examiner, and, I might add, at the expense of their own tax dollars.”

“Great. You’re the boss. So are you going to tell this to those Dane guys, or am I gonna have to do that too?”

“I’ll take care of that, Jan.” Helen’s face suddenly flushed with embarrassment and self-disgust. But she was only doing her job. Why couldn’t Beck understand that? Olsher would pull the plug on this first thing in the morning; arguing about it was a waste of time. “There’s nothing I can do, Jan. And you know that. So stop breaking my chops.”

Beck made the most minute of nods. “Christ, it’s just that sometimes I get so sick of it.” She glanced back at the techs hovering over the baby. “I can’t believe the things that people do.”

“Neither can I,” Helen feebly replied.

Beck managed a twisted smile. “Well, at least we got some payback today, huh?”

“What do you mean?”

“You know. The Dahmer thing.”

Helen winced against a chilling waver of wind. “What? What about Dahmer? That son of a bitch is locked up for the next thousand years.”

“Didn’t you hear?” Jan Beck asked. “We all got the telex this morning.” She seemed to thrive on the cold, she seemed enlivened by it, or perhaps she was only enlivened by the news she’d heard.

“Jeffrey Dahmer,” she explained, “was murdered in prison today.” Another tiny twist of a smile. “He was bludgeoned to death by another inmate.”

— | — | —

CHAPTER TWO

“…bludgeoned to death by another inmate,” the radio squawked. “James Dipetro, director of the 676-man Columbus County Detention Center, where the infamous cannibalistic murderer was serving a 936-year sentence, told reporters that he fears the suspect, one Tredell W. Rosser, may now be regarded as a celebrity by the prison’s other minority inmates. ‘We fear,’ Dipetro said, ‘that Rosser will become a prison folk hero of sorts, and not just by Columbus inmates but by every Hispanic and African American convict in the country…’“

Helen, in pre-8 a.m. rush hour, switched the radio station. Dahmer, Dahmer, Dahmer, her thoughts complained. The news dominated every radio station she turned on, and morning tv hadn’t been any better. Jesus Christ, is that all anyone cares about? Dahmer? I’m absolutely SICK of hearing about him!

But if that were really the case, why was Helen driving to the state morgue to see the body?

««—»»

The man walks down the sun-lit street, in Madison, Wisconsin. Bright light but cold, like his heart. The chill air whips his face, yet he feels numbly warm. The city seems to swarm around him, not part of him, and he not part of it. But that’s how it always is. He ducks out; he doesn’t want to be on the street too long. He doesn’t want to be seen.

Some time later, he finds himself walking up a flight of stairs, each footfall slow and plodding and deliberate. He feels different now, like some odd toggle in his brain has been switched. Nevertheless, each step he takes upward takes him back…

««—»»

BATH, OHIO, MAY, 1971

The boy from Bath, Ohio.

What a dumb name for a town, he always thought. But right now he was thinking about things far more crucial.

Spring heat cooked his back. His sweat drenched his shortsleeve, plaid shirt as he ran, yes, ran in spite of the prickling heat—hoping to get home before his father did. He cut through yards, the long way, to get home from school every day. He couldn’t stand to be taunted by the other kids. Faggot, they called him. Pussy. In phys ed, the captains had been choosing up teams. Gil Valeda, who was probably the best athlete in the fifth grade, if not the best in all of Summerset

Elementary, laughed when the boy had jerked his hand up, wanting to be, for once, on a winning team. “No way,” Valeda had said. “You’re a weakling, a little faggot.” The boy had been chosen by the other side, last pick. They’d lost the softball game 11 to nothing. His other teammates had blamed him, of course, for striking out three times, for dropping a ball in right field.

He pretended not to hear, and not to care.

But he really did care.

And one day, he knew, he would show them all…

««—»»

I’m free, he thought.

And he was hungry.

««—»»

“…bludgeoned to death with a broom handle,” another radio announcer was spewing in an automaton’s voice. “Authorities say that the murder occurred at approximately eight a.m. yesterday, when Dahmer was on a custodial detail in the gymnasium of the Columbus County Detention Center. Prison guards discovered a bloody broom handle nearby, and another inmate, reportedly a friend of Dahmer’s, was beaten also, and is now listed in critical condition at St. John the Divine Hospital in Madison. Officials say that Dahmer’s face was beaten so severely that—”

Helen changed radio stations yet again, trying to edge her way to the state employees lot. Tom had left a message on her answering machine. “Hi, Helen, it’s me. I won’t be getting off at seven this morning, I’ve been ordered to stay on. You’re never gonna believe this—Greene’s on vacation, so I’m the Acting Chief Medical Examiner while he’s gone. What I mean is I’m the one who’s going to autopsy Dahmer’s body! See ya tonight!”

Even Tom seemed to have the bug. What was the fascination? Perhaps it was Helen’s job that bored her on the topic; she saw death every day, and killers, to her, were all one in the same. They were the active statistics on a grim social spreadsheet, numbers that produced other numbers. She could think of it in no other terms: victims as well as perpetrators could never be humanized by the homicide investigator. Otherwise that homicide investigator would burn out in a year or two and wind up contemplating suicide every day. Last night’s 64 proved a case in point; if Helen thought of the decedent as a baby, a kid, a human child, etc., the freight of that humanity would wring her dry. It would wring anyone dry, she thought. To her, that baby could only be this: a homicide stat, a number on a very dark piece of paper.

It made her feel so cold, though, thinking about it at times like these. Maybe she was lying to herself; she’d done that a lot in her life. Acting one way but actually feeling another. How much longer could she pretend not to feel, if this were truly the case? She remembered the day Deputy Chief Olsher had barged into her office with a smile like a great, black pumpkin, and told her that Henry Longford had been diagnosed with inoperable brain cancer. Longford had run a sophisticated point-network for the distribution of child pornography; Helen, working liaison with the Justice Department, had helped send Longford up to the Federal Max in Marion, fifteen years with no parole. “See, Helen?” Olsher reveled. “There really is a God. That sick piece of garbage’ll be dead before he’s even got five under his belt!” Helen’s initial reaction had been one of stoic nonchalance. She’d responded with something like: “Right now I’m too busy to even think about Longford.” Something like that, which sent Olsher away with the oddest expression. When she’d gotten home, however, she’d begun crying in fits, slowly but surely remembering the tiny, washed out faces in all those video masters, the nine-year-old thousand-yard stares. Eventually her sobs meshed with an hour-long paroxysm of manic laughter. It was strange what this job would do to people.

St. John the Divine Hospital was just south of Madison, and there, occupying half of its basement, was the Office of the Wisconsin State Medical Examiner along with the WSP Main Crime Lab. Tom’s workplace, and Beck’s. But Helen noted an immediate curiosity. Why bring Dahmer’s body here? she asked herself. Upon sentence, Dahmer had come into the correctional custody of the County of Columbus, whose own M.E. facilities were at South Columbus General just outside of Portage. Why call in the state M.E.?

Helen had to show her badge and ID three times just to get through the ER wing—she avoided the north entrance upon noticing an influx of news hawks and cameras—and three more times just to get downstairs. Why all the heat? There were cops everywhere: state troopers as well as a lot of Madison Metro PD. In the basement she first passed the lock-up wing, a little ICU prison for injured inmates and arrestees. PREPARE TO BE MAGNOMETERED UPON ADMITTANCE. LAW ENFORCEMENT EMPLOYEES CHECK WEAPONS IN WITH PROPERTY OFFICER HERE. Her high heels ticked across shiny tile; at the end of the corridor, another sign announced: WISCONSIN STATE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH, MADISON SUBSTATION. Then, a final plaque: MORGUE.

“Helen!” Tom greeted when she entered. She’d been ID’d a final time at the recept desk. “I would’ve thought you’d be home asleep.”

“I couldn’t sleep,” she admitted. Intermittent nightshifts played havoc with her metabolism, but it must for Tom too. Nevertheless, he looked cheery and alert in his disposable autopsy blues. Helen had tried to sleep upon her return from the Farland call, but the pallid nightmare-face had kept hounding her. Waxlike, exsanguinated. When the cool, claylike hands had dipped to touch her bare breasts, she’d bolted awake and gave up on any further attempts to sleep.

“I’d come over there and kiss you,” he joked, “but, as you can see, I’m sterile.”

“What difference does it make to cadavers?”

“State regs, hon. Pretty soon the cadavers’ll be suing us—and winning. You got my message, I take it.”

“Yeah,” she said. “Say, what’s with all the heat? It was like trying to get into the Pentagon.”

“Aw, you know. Something like this, press fodder? I’ve even got a trooper guarding the back entry. They’ve caught six people already trying to sneak in here.”

“For what?”

“To get a picture of the body. One guy tried to steal his inmate number off his prison coveralls, another guy said he wanted to steal one of his teeth.”

This was ridiculous. “Dahmer’s teeth?”

“Sure,” Tom said, pulling out a box of Johnson & Johnson Morgue Swipes. Kills E. Coli and Other Morgue-Related Bacteria on Contact! Kills Herpes, Hepatitis B and HIV! the blue and white box bragged. “I’m amazed by the level of detail that the press has got their hands on. Christ, Columbus County Detent leaks like a sieve. Most of Dahmer’s teeth were broken; this guy says he heard it on the radio, thought he’d zip in here real quick and cop one of the teeth. They charged him with trespassing on state property and ‘morbid malfeasance.’“

“Jesus,” Helen dismissed. “They ought to charge him with being an asshole too, but I don’t think that one’s in the state books.”

“Not yet, anyway, but we can always hope.”

So that explained the undue police presence, which miffed her right off the bat. These cops had better ways to serve the public interest than guarding a corpse. Right now, on Clay Street, crack was being sold. Right now in the stan district, heroin tar was being cut. Right now, somewhere, a woman was being raped.

In the prep room, Helen at once found herself hemmed in by dented file cabinets, bookshelves, and a lot of computer equipment. One CPU, she noted, was a UNISYS 1500 latent datalink, which had state and federal mainframe access to every felon fingerprint in the country. A small, glass scan-pallet would digitalize the latent and feed it into the system. Cost per unit: $650,000. Too bad it crashed regularly. An equally expensive mass photospectrometer ticked in the corner like a cooling car engine.

A chuckle, then: “Mix you a drink?” Tom was mixing a formalin/alcohol mixture in several big translucent squeeze bottles: cadaver preservative. Helen hated the smell of formalin; it was the only thing that gave her a headache worse than tequila.

“So how’d that 64 go last night?”

“Terrible. It was a baby,” she finally told him. “Beck was there, as usual, and she was all over me. There was no way in hell that I could’ve writt

en up for VCU. I don’t understand it. Beck hates me.”

Tom was wincing immediately, which mystified Helen. But before she could even ask, a figure appeared from the dressing room, dressed in the same disposable morgue blues. It was Jan Beck.

“I don’t hate you, Captain,” she said. “I was just bent out of shape last night, and I apologize.”

Good job, Helen! She felt like a perfect ass, but the scenario infuriated her. What the hell is Beck doing here! she wanted to shout.

“Jan’s doing the assist,” Tom explained. “I think I told you on my message, Greene’s on vacation as of last Sunday, went to Bowie, Maryland, or some hole in the wall town like that. I’ll bet he’s crapping his blues right now.”

Helen’s face screwed up. “What, autopsying Jeffrey Dahmer is a big deal?”

“My dear, in the world of forensic pathology, receiving the opportunity to perform the post-mortem on a world-famous serial-killer is a career event.”

Beck laughed. Helen rolled her eyes.

“I’ll be ready to roll in a few minutes,” Tom said more to Beck. “I’ve gotta let the instruments cook a little longer in the ‘clave.” His eyes gestured the Magna brand 260-degree autoclave percolating in the corner like an industrial washer. Helen thought it absurd to have to sterilize instruments that would be used on dead people. Tom had said the machine cost the state over $4000. I could do the same job with a boiling pot of water, Helen thought.

“Come on,” Beck implied to Helen, and a wave of hand. “Let’s go look.”

“Go look at what?” Helen replied.

“You know. The body.”

“I didn’t come here to see the body,” she insisted.

“Oh, yeah, then why are you here? Let me guess. You came all the way to the state morgue to ask Tom what he wants for dinner tonight?”

A brief impulse flared. First of all, Helen didn’t like the way Beck had so easily referred to Tom by his first name; second, she liked least the fact that it was common knowledge she and Tom were dating, an unwritten no-no for state employees. But then the good Dr. Sallee’s remonstrations kicked in, as they usually did. You’re so insecure, you’re paranoid. You over-react to everything. You have to work on this, Helen. You must, or you’ll never be happy.

In the Year of Our Lord 2202

In the Year of Our Lord 2202 The Minotauress

The Minotauress Terra Insanus

Terra Insanus The Stickmen

The Stickmen Flesh Gothic by Edward Lee

Flesh Gothic by Edward Lee Family Tradition

Family Tradition You Are My Everything

You Are My Everything The Backwoods

The Backwoods The Teratologist

The Teratologist Smoke and Pickles

Smoke and Pickles Buttermilk Graffiti

Buttermilk Graffiti Dahmer's Not Dead

Dahmer's Not Dead Quest for Sex, Truth & Reality

Quest for Sex, Truth & Reality The Innswich Horror

The Innswich Horror Brides Of The Impaler

Brides Of The Impaler Goon

Goon Trolley No. 1852

Trolley No. 1852 Sacrifice

Sacrifice Monster Lake

Monster Lake Succubi

Succubi Lucifer's Lottery

Lucifer's Lottery Monstrosity

Monstrosity The House

The House The Dunwich Romance

The Dunwich Romance Operator B

Operator B Bullet Through Your Face (improved format)

Bullet Through Your Face (improved format) Grimoire Diabolique

Grimoire Diabolique Room 415

Room 415 The Messenger (2011 reformat)

The Messenger (2011 reformat) Incubi

Incubi The Black Train

The Black Train House Infernal by Edward Lee

House Infernal by Edward Lee City Infernal

City Infernal Creekers

Creekers The Haunter Of The Threshold

The Haunter Of The Threshold Mangled Meat

Mangled Meat The Doll House

The Doll House Header 2

Header 2 Bullet Through Your Face (reformatted)

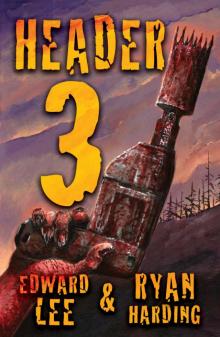

Bullet Through Your Face (reformatted) Header 3

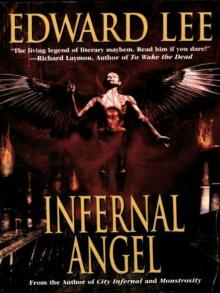

Header 3 Infernal Angel

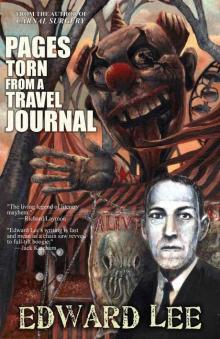

Infernal Angel Pages Torn From a Travel Journal

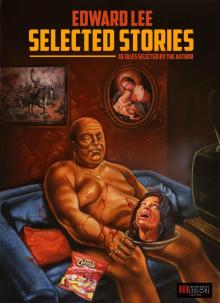

Pages Torn From a Travel Journal Edward Lee: Selected Stories

Edward Lee: Selected Stories The Bighead

The Bighead The Chosen

The Chosen