- Home

- Edward Lee

Dahmer's Not Dead Page 2

Dahmer's Not Dead Read online

Page 2

“Dahmer, hey, Dahmer,” Rosser taunted. “What human meat taste like?”

“Shut up, Rosser,” Wells ordered. Dahmer remained silent, shuffling along next to Vander. Vander’s bald head gleamed in the caged line lights. “Don’t listen to him, J.D.,” Vander said aside. “He’s an asshole.”

“Dahmer, hey, Dahmer—”

“Goddamn it, Rosser, I said shut up,” Wells repeated. “You don’t and I throw your big bad killin’ ass straight back into bev-seg where you can count the lines in the cinderblocks for twenty-three and a half hours a day.”

“Ain’t no cell on earth can hold the Son of God,” Rosser whispered. “You are the number of the beast, and that number is six-hundred, three score, and six.”

“Cut with the Ganser shit. You’re just making an asshole of yourself.”

“You callin’ the Son of God an asshole?”

Wells couldn’t help but laugh. He followed them up into the gymnasium, then pointed out their assignments. “Vandie, J.D., you two split between the weight room and the treadmill cove, and Rosser, you mop the latrine. Got it, guys?”

Dahmer and Vander nodded. But Rosser? No way. He’d always be running his yap about something. “Aw, man,” he complained. “You’re gonna make the Son of God mop the latrine, man?”

“That’s right.”

“But-but, I am the million-year-old Son of God!”

“Fine,” Wells said. “And you’re gonna get that latrine so clean that God Himself would happy to drop His poop in our bowls, so tell that to your Dad. I’ll be right outside but I got my eye on all of ya’s. Get the job done and no dicking around.”

The three inmates dispersed with their forlorn buckets and mops. Wells went back out on the main line, tapped out a cigarette.

No sign of Perk. Christ, I wonder how bad the Redskins lost yesterday. Wells had a fin on a tight spread, but Shuler was looking hot.

Early morning, the main line seemed oddly quiet, a Zombieville of shuffling men all dressed in the same muck-green prison utilities and all wearing the same drained faces. Wing sectors of four to six men each were being escorted to and from chow. Wells thought it was funny; this morning Dahmer had eaten only one hard-boiled egg—he ate the egg white only, leaving the solid yolk—and some cereal with no milk. Said he was on a diet, of all things. Who the hell do you need to look good for? Wells thought. The wall?

Wells drably smoked half his cigarette, then tamped it out in the red butt-can. Perkins must be on drive detail, escorting inmates to the county courthouse in downtown Portage.

About ten minutes later, at precisely 8:10 a.m., DO Wells turned to go back to his supervisory post, but he didn’t even have time to finish the turn before the lock-down alarm began to blare through the prison like an air raid siren, so loud that even the dense block walls seemed to throb outward with each blast. The prison was having a heart attack.

««—»»

The nightmare-face hovered so close she could smell it. Yet it didn’t smell real, it didn’t smell human. Like clay, it smelt, like damp, creeky earth. The face seemed gray in the dream, as though its features had been crudely gouged from a blank of—indeed—clay. A slit for a mouth, a slit for nose. Twin slits for eyes. But whose face was it?

Help me, help me! she squealed amid the REM-sleep turmoil. Get it away from me!

It was the insuccinct face of any cop’s fear, the face of the symbolic death that waited around every corner.

“Helen? Helen?”

The jostling felt earthquake-like. The walls of her dream vomited sound akin to echoic demolition. The hand, from another world, continued to nudge her.

“Helen?”

Her eyes slid open. Now, another face, just as obscure, hovered above her, just as pale and as inhumanly defeatured. Her mind seemed to slide with the unbidden opening of her eyes. Then the real world cleared as did the visage. Of course, it was Tom.

Immediately she caught herself rubbing the silver locket between her fingers. It was a big locket, big as a Bicentennial dollar, and deep. It had her father’s picture inside. Through a variation of necklaces, it had hung around Helen Closs’ neck for close to three decades, a present her father had given her on her thirteenth birthday. “Welcome to teenagerhood!” he’s celebrated. He’d died the next day, a massive coronary at the realty office he owned.

“Honey, are you all right?” Tom asked.

Why shouldn’t I be all right? her first thought hastened. If I’m not all right, it’s only because you just woke me up.

“You’ve been sleeping since eight this morning.”

“I know,” came her graveled reply. “I worked a nighter last night.”

“Well, so did I but…”

Her shoulders jerked, as if to verify she was no longer asleep. “But what?”

“Well, I worked a nighter too, but, Christ, honey, it’s past seven now. I got up hours ago.”

And what did that mean? Her attitude, as always, honed to knife-sharpness fast as current through a copper wire. What’s he implying? “What?” she challenged. “I sleep till seven and that means I’m just a lazy, over-the-hill cow?”

Tom’s countenance gave up its expression of concern and immediately reverted to something terribly weary. But of course, she’d seen it many times before. “Aw, come on, Helen, get off that, will you? I’m not saying you’re lazy, I’m just a little worried. You never sleep so long. I was worried that maybe you’re sick.”

Helen’s gaze focused upward.

“You really are making this hard,” he said. Then he walked out of the bedroom.

She simpered were she lay. A conflux, then, of more realities. I slept for eleven hours? Jesus Christ, get a life, Helen! And she’d screwed it up again, hadn’t she? It seemed miraculous that Tom hadn’t written her out of his life months ago, considering her bitchiness. I snapped at him again, she realized, and all for what? Because he was worried about me. How many past relationships had provided the exact opposite? One rough spot after the next; after so many rough spots, they’d cut you loose. And why shouldn’t they? Who needs a bitchy headache like me?

Now the rest came back. She’d gotten off her shift at seven a.m., and come to Tom’s, to sleep with him. Staggered shifts didn’t make things easier, but the state medical examiner’s office had swing shifts too. Tom was number-one deputy at the M.E.’s; he’d pull nighters one week out of every three. They’d been “dating” for a year and a half, whatever “dating” meant.

It’s always the same. What was wrong with her? Pre-menopausal Anxiety. Or maybe I’m just a genetic bitch, she considered. Her hormones and mood swings weren’t Tom’s fault. “Menopause can be interpreted as the physical death of a woman’s femininity,” Dr. Sallee, the state police shrink, had told her. “But it’s important for you to realize that this is a misinterpretation, rooted in fear. It’s something women constantly fear only because of the basic tenets of fear itself.” Sallee’s face often appeared similar to the face in her recurring nightmare. “Yes, you will be menopausal soon, but menopause does not signify the death of your womanhood. All it signifies is a new stage of your femininity, a new stage of life. Not a negative at all, but a positive.”

At least he had a way with words. But it was hard for her to perceive Tom as anything but her last hope. She was 42—how much time could be left? Her first husband turned out to be such an asshole she was surprised she didn’t kill him. And the relationships which followed? One botch after the next. She knew that if she ever hoped to be married again, Tom was the one. But if she didn’t get a rein on her “pseudo-natal hostility,” as Dr. Sallee called it, she’d blow it with Tom too. And that would be the last straw.

She dragged herself out of Tom’s bed, scurried to the bathroom to gargle and fix her mussed, off-blond hair. Then she scurried just as hastily to the den. Tom sat behind his new Compaq computer, playing one of his CD-ROM games. He was so immersed that he didn’t take note of her entrance, and—

Who could blam

e him? Helen wondered. I wouldn’t notice a bitch like me either…

The X-Wing Fighter crashed, just short of knocking out the Demon Planet’s power duct, when she came up from behind and put her arms around him. Terrifying explosions resounded from tiny speakers. “Well, you just killed Captain Quark,” he said.

“You can bring him back to life in the next game,” she reminded him. “Besides, he’s not as good-looking as you are anyway.”

Tom chuckled distantly.

“I’m sorry,” she leaned over, whispered in his ear. “I’m sorry I’m such a bitch all the time. I didn’t mean to snap at you.”

“You didn’t snap,” he said in a tone that actually meant, Yes, you did but I’m used to it now, so I forgive you. “I was just worried. I thought you might be sick. Are you all right?”

“Except for the case of Acute Bitchism, I’m fine.” She kissed the top off his head. “How about I treat us to Chinese? You can even bring Captain Quark back from the dead, and I’ll go pick it up.”

“Wow, a woman who pays for dinner and picks it up? Now that’s a woman!”

“Don’t forget the part about being good in bed.”

“Well, of course, but that goes without saying,” he admitted, jiggling his Mouse Systems joystick. “I could go for some Kung Pao, and those little shrimp things.”

“I believe the shrimp things are called Shrimp Toast,” she corrected.

“Yeah, right, but… What time’s your shift?”

She pressed her breasts against the high part of his back. The pressure seemed to send a gust of sensation to her loins. I’ll jump his bones good tonight, she avowed. I’ll make it up to him. “I’m off tonight,” she said.

“Oh yeah?” He looked around. “That’s great—”

And then her beeper went off. I’m also on call, she remembered. When you make captain for VCU, you’re on call for the rest of your life.

“Aren’t you going to answer?” he asked.

“I really don’t want to. Goddamn it, I fucking hate this shit.”

As usual, Tom recoiled a bit at her profanity. “You better call in.”

“I know.”

She padded to the kitchen, hesitantly picked up the phone, and called Central Commo. Waited. Listened.

“Goddamn it, I hate this shit!” she reiterated.

“What’s wrong?”

“I just got a 64 in Farland.”

“The boonies. Is it bad?”

“If it weren’t bad, Dane County wouldn’t be calling me into their juris. Shit!”

“So…what’s the 64?”

“A—” she began and that’s where she left it. He didn’t need to know, and she didn’t want to repeat what Central Comm had just told her: the victim was an infant. “It’s just…bad, as usual.”

But that was Helen’s job: the bad ones, the ones too intensive or excruciating for the local departments to handle on their own.

She hurried to take a two-minute shower, hauled on her dress and her Burberry overcoat—a very nice coat that Tom had given her last Christmas. Then she was hustling out with her hair still wet.

“Don’t I get a kiss?” Tom asked. He stood ready at the door, surprising her. Then he kissed her on the mouth and embraced her in a tight, warm hug.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered again.

“Hey, the Kung Pao can wait, and so can those shrimp things.”

“No, I mean about before.” And then his own words haunted her: You really are making this hard. She knew she was, she knew it all too well. Her entire adult life was proof.

He was so cute, so handsome. Short, dark hair; deep, penetrating eyes full of compassion and intellect. He had a rampant sense of humor too, unlike her former husband who was about as upbeat as Jean Paul Sartre. Tom could joke away the worst stress headache or post-shift blues.

Her own eyes opened on his softly smiling face, and she nearly melted. I don’t deserve him, she thought, but then she could hear Dr. Sallee berating her all the way from HQ.

“You’re going to rub that thing into non-existence,” he warned.

What? she wondered, then she realized: she was rubbing her locket again, pressing hard. Over the years she had indeed rubbed off quite a bit of the surface detail.

“You always rub that locket when you’re upset.”

“I’m not upset,” she countered.

“Well, when you’re stressed out, worried, whatever. Why?”

She didn’t answer directly because she couldn’t. But she guessed he was correct. The locket was her Linus blanket, her rabbit’s foot, she supposed. “It’s like a good luck charm, and I’m probably gonna need it tonight.”

“Still don’t want to tell me about that 64 in Farland?”

“No,” she asserted. But the words were still there, flotsam in a dark sea. A baby. Someone killed a baby… But people killed babies every day in this demented age. It’s my job to investigate murder, she scolded herself. She let go of the locket. So go do it and stop being such an insecure wuss.

“Go on, get out of here,” Tom said. “You can’t keep public service waiting. Do you have your gun?”

“Yes,” she groaned. Helen hated guns but she had little choice but to carry one. A tiny Beretta Jet-Fire, .25 ACP. She was so bad at the range she had to be waived every year to qualify.

“Good. And be careful, okay?”

“I will.” She could tell, as she always could, that here was a man who was genuinely concerned with her, and someone who genuinely loved her. Don’t screw it up again, Helen, she warned herself.

She kissed him again and left.

««—»»

Dane County didn’t have its own PD—they were uncharted, like a lot of Wisconsin’s counties. What they had instead was a small-time sheriff’s department. Helen’s response grid—Grid South Central—stretched from Beloit to the Petenwell Reservoir; this one, at least, wouldn’t be too bad of a drive in her unmarked. There’d been times when she’d had to take the pill-white Ford Taurus a hundred miles out of Madison merely to write up a prelim WSP Form 18-82—Initial Investigatory Report for Possible Critical Case Homicide—and then recommended as to whether or not the 64 warranted the intervention of the Wisconsin State Police Violent Crimes Unit. VCU was run by six regional field liaisons, all captains, one of whom was Helen Closs. Eighteen years with the state police, she’d started at Traffic and worked her way up. Three years ago, working with the Intelligence Unit, she’d orchestrated a state-wide sting operation that had brought the house down on a complex cocaine triad whose shooters had murdered half of their informant line as well as four state undercover cops. Result: promotion to captain, commendations from the governor and the director of the DEA, and a transfer to the coveted VCU. The unit let her work alone, make her own decisions, and left CES and Processing at her instant disposal. Thus far, of the seventeen critical homicides that had taken place in her grid, Helen had solved sixteen, the highest success percentile in the history of the department. In another year, she’d be up for deputy chief.

A grand career, in other words. Yet grand was the last thing she felt. Forty-two, she thought dryly, and premenopausal according to my blood tests. One bum marriage and half a dozen bum relationships. Was it age, or just the world? The world was a vampire whose lips and fangs sucked up a little bit more of her vitality as each year passed. A world of murderers and child molesters, of Fetal Cocaine Syndrome and gang rape and failure. She hadn’t truly seen the sun shine in twenty years.

Just darkness, and the ebon of the human mind.

A plethora of visibar lights erupted as Helen pulled up at her 20. State Technical Services looked like scarlet phantoms roving the darkness; Sirchie portable UV lamps glowed eerily purple. The techs wore red polyester utilities so that any accidental fiberfall wouldn’t be confused as crime-scene residue by the Hair & Fibers crew back at Evidence Section.

Cold air choked her when she got out of the Taurus’ capsule of heat. Her breath turned to dismal gaseous

frost. A long county road—ravined and flawlessly straight—seemed to extend into infinity. A couple of Dane County Sheriff’s cars—old Ford Tempos—sat parked off the road in a vast cornfield that had been threshed to nubs a few months ago, their headlights aimed at the contact perimeter. Three state cars were here too; on any case that might qualify as a VCU candidate, Central Communications would dispatch the nearest state units, to help the local department secure the scene, and CES had been dispatched right after them, a powder-blue van which served as a mobile crime lab, and a couple of station wagons the same odd color. The uniforms, both county and state, seemed oblivious to the cold, unjacketed as they leaned against their cars.

“Captain Closs?” one voice rang out.

Helen showed her badge and ID to the corporal who approached her, a young guy from Highway Division.

“Is Beck here?” she asked, turning up her collar.

“Yes, ma’am.” He pointed to the lit ravine. “Down there. It’s…”

“What, Corporal?”

“It’s pretty bad, ma’am.”

Helen ignored the comment, glancing instead up toward the county cars. Several of the men were smoking. “Tell those idiots from Dane to put there cigarettes out and pocket the butts. Jesus Christ, this is a crime scene.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“And if I see any state cops smoking here, I’ll write them up. I’ll make the Wicked Witch of the West look like Little Orphan Annie. Got it?”

The corporal nodded, his face whitened raw by the cold. Or perhaps it was really shock. After all, there was a dead infant somewhere on this perimeter.

Helen squinted again at the county responders: a mopey, ragtag bunch. “I mean, what is this? The Keystone Cops?”

“Those county SD guys? They don’t know what to do, that’s why they called in a VCU request when they found the body.”

The body, Helen finally remembered why she was here. The baby. “Who’s the trooper in charge? You?”

In the Year of Our Lord 2202

In the Year of Our Lord 2202 The Minotauress

The Minotauress Terra Insanus

Terra Insanus The Stickmen

The Stickmen Flesh Gothic by Edward Lee

Flesh Gothic by Edward Lee Family Tradition

Family Tradition You Are My Everything

You Are My Everything The Backwoods

The Backwoods The Teratologist

The Teratologist Smoke and Pickles

Smoke and Pickles Buttermilk Graffiti

Buttermilk Graffiti Dahmer's Not Dead

Dahmer's Not Dead Quest for Sex, Truth & Reality

Quest for Sex, Truth & Reality The Innswich Horror

The Innswich Horror Brides Of The Impaler

Brides Of The Impaler Goon

Goon Trolley No. 1852

Trolley No. 1852 Sacrifice

Sacrifice Monster Lake

Monster Lake Succubi

Succubi Lucifer's Lottery

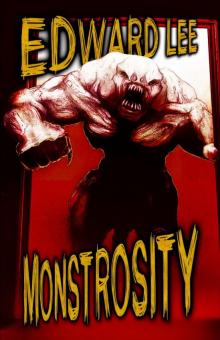

Lucifer's Lottery Monstrosity

Monstrosity The House

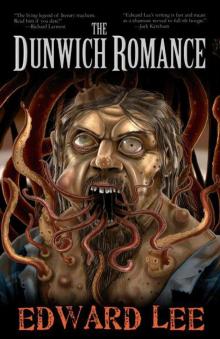

The House The Dunwich Romance

The Dunwich Romance Operator B

Operator B Bullet Through Your Face (improved format)

Bullet Through Your Face (improved format) Grimoire Diabolique

Grimoire Diabolique Room 415

Room 415 The Messenger (2011 reformat)

The Messenger (2011 reformat) Incubi

Incubi The Black Train

The Black Train House Infernal by Edward Lee

House Infernal by Edward Lee City Infernal

City Infernal Creekers

Creekers The Haunter Of The Threshold

The Haunter Of The Threshold Mangled Meat

Mangled Meat The Doll House

The Doll House Header 2

Header 2 Bullet Through Your Face (reformatted)

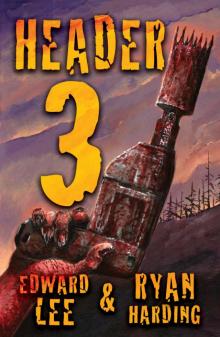

Bullet Through Your Face (reformatted) Header 3

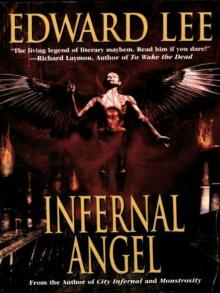

Header 3 Infernal Angel

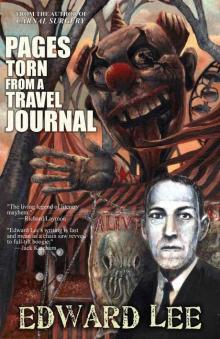

Infernal Angel Pages Torn From a Travel Journal

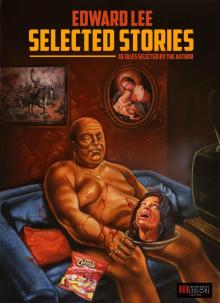

Pages Torn From a Travel Journal Edward Lee: Selected Stories

Edward Lee: Selected Stories The Bighead

The Bighead The Chosen

The Chosen