- Home

- Edward Lee

Succubi Page 5

Succubi Read online

Page 5

“I’ve told you, dreams mix symbols with our outward, objective concerns. Here, the symbol is obvious.”

Was it? “I’m a lawyer,” Ann stated. “Lawyers think concretely.”

Dr. Harold’s eyes always appeared bemused. He had a pleasant face with snow white hair, and big bushy white eyebrows and a bushier white mustache. He spoke slowly, contemplatively, placing words like bricks in a wall. “The symbolic duality,” he said. “Life and death. The notion that you almost died while creating life. The proximity of utter extremes.”

Life and death, she thought. “It was borderline pneumonia or something like that. Thank God Melanie was okay. I was barely conscious for about two weeks after the birth.”

“What do you remember of the birth?”

“Nothing.”

“It’s pretty clear, then, that the dream is dredging up aspects of Melanie’s birth that were infused into your subconscious mind. Think of it as a spillover, from the subconscious into the conscious. We call it ‘composite imagery.’ Your mind is trying to form a real picture of Melanie’s birth with unacknowledged memory fragments.”

“Why?” Ann asked.

“Why isn’t nearly as important as why now. Why is this occurring at this precise point in your life? Let me ask you, was Melanie a planned pregnancy?”

“Yes and no. We wanted a child, that is.”

“You had no reservations, in other words?”

“No, I didn’t. I think my husband did. He didn’t think we could afford to have a child, and I’ll admit, things were pretty tight. He never made much money, I was young, nineteen, I was pregnant in my first year of college, and I was determined to go to law school afterward. I think maybe one reason I wanted a child was because I thought it would make our marriage stronger.”

“You considered your marriage weak?”

“Yeah. I honestly wanted it to work, but now that I think of it, I guess I wanted it to work for the wrong reasons.”

Dr. Harold raised a bushy white brow.

“I don’t like failure,” Ann said. “Mark and I probably never should have gotten married. My parents couldn’t stand him, they were convinced the marriage would fail, and I suppose that fueled my own determination to see that it didn’t. They were also convinced that I’d never make it through law school. Their discouragement was probably my greatest motivating factor. I graduated third in my class. I waited tables at night, went to school during the day. I missed a semester of college to have Melanie, but I made up for it and then some by taking a heavier credit load afterward. In fact, I graduated a year early even with the missed semester.”

“Impressive,” Dr. Harold remarked. “But I’m more interested in your parents. You’ve never mentioned them before.”

“They’re a bit of a sore subject,” Ann admitted. “They’re very old fashioned. They wanted me to assume a traditional female role in life, clean the house, raise the kids, cook, while hubby brought home the bacon. That’s not for me. They never supported my desires and my views, and that hurt a lot.”

“Do you see them often?”

“Once every couple of years. I take Melanie up, they love Melanie. She’s really the only bond at all that exists between me and my parents.”

“Are you on good terms with them now?”

“Not good, not bad. Things are much better between me and Dad than me and Mom. She’s a very overbearing woman. I think a lot of the time, Dad was all for my endeavors but he was afraid to express that because of her.”

Dr. Harold leaned back behind the plush veneered desk. “Another parallel, a parental one.”

Ann didn’t see what he meant.

“There’s a lot of guilt in you, Ann. You feel guilty that you’ve put your job before your daughter because you feel that in doing the opposite, you’d satisfy your parents’ convictions of occupational failure. More important, you feel guilty about neglecting to support Melanie’s social views. Your own mother neglected to support your social views. You’re afraid of becoming your mother.”

Ann wasn’t sure if she could buy that. Nevertheless, she felt stupid for not considering the possibility.

“Since the day you left home, you’ve been torn between opposites. You want to be right in the traditional sense, and you want to be right for yourself. You want both ends of the spectrum.”

Was that it?

“You’re very unhappy,” Dr. Harold said.

I know, she thought. It depressed her that he could read her so easily. “I need a solution,” she said. “The nightmare is ruining me. I’m not getting enough sleep, my work is slipping, I’m in a bad mood when I get home. Don’t you guys have some wonder drug I could take that would make the nightmare stop?”

“Yes,” Dr. Harold said. “But that wouldn’t solve any of your problems; it would only cover them up. You’re having the nightmare for a reason. We must identify that reason.”

Dr. Harold was right. There was no quick fix.

“How is Martin taking all of this?”

“Better than most guys would. I know it’s hard on him. He’s not getting any sleep either, because I’m always waking him up during the dream. He’s pretending that it’s no big deal, but it’s starting to show.”

“More fear.”

“What?”

“More fear of failure. You’re afraid of failing with Melanie, and you’re afraid of failing with him. You’re afraid at the end of your life all you’ll have to show for your existence is selfishness.”

“Thanks.”

“I’m merely being objective. You love Martin, don’t you?”

“Yes,” she said with no hesitation. “I’d do anything for him.”

“Anything except marry him. Still more fear.”

Jesus Christ! she thought.

Dr. Harold smiled, as if he’d read the thought. “You’re afraid that Martin thinks you’re holding your first marriage against him.”

“He’s suggested that himself. Is it true?”

“It seems to be quite true.”

This was depressing. Coming here didn’t make her feet better, it made her feel worse. “What am I going to do?”

“The first thing you must do is be patient. You’re a very complex person. Understanding your problems will be a complex affair.”

Tell me something I don’t know, Doc.

“The images and ideas expressed in dreams function in two fundamental modes,” Dr. Harold went on. “One, the manifest mode, which relates to the content as it occurs to the dreamer, and, two, the latent mode, the dream’s hidden or symbolic qualities. The dream is about you giving birth to Melanie. There’s a strange emblem in the dream, there’re dark, hooded figures and cryptic words like incantations. The dream sounds almost satanic. Dreams of devils often signify a rebellion to Christianity. Are you a Christian?”

“No,” Ann said.

Dr. Harold smiled. “Are you a satanist?”

“Of course not. I’m not anything, really.”

“You’re saying you were raised with no religious beliefs at all?”

“None.”

“Don’t you find that strange, especially with the traditional sentiments of your parents?”

“It is strange,” she agreed. “I was born and raised in Lockwood, a small town up in the northern edge of the county, up in the hills. Only about five hundred people in the entire town. There was a big church, everyone attended every Sunday. Except my parents. It was almost like they deliberately shielded me from religion. They kept me blind to it. I really don’t know much about religion.”

“What about your daughter?”

“The same. I try not to influence her that way. I wouldn’t know how to even raise the subject.”

Dr. Harold contemplated this. He remained silent for some time, looking up with his eyes closed. “The dream is definitely about an array of subconscious guilt. How can you feel guilty about a religious void when you’ve had virtually no religious upbringing?”

“I

don’t,” Ann stated.

“And you don’t feel that a religious belief might help Melanie become better rounded in life?”

“I don’t think so. I don’t see how it could. She’s never been a problem that way.”

“Is she a virgin?”

The question stunned her. “Yes,” she said.

“You’re sure?”

“As sure as I can be, I suppose.”

“Do you find that unusual?”

“Why should I?”

“The average first sexual experience for white females in this country occurs at the age of seventeen. Did you know that?”

“No, I didn’t.” Ann, see if you can guess the next question.

“How old were you when you had your first sexual experience?”

“Seventeen,” Ann replied, though None of your fucking business would’ve been a better reply. “What’s that got to do with it?”

“Isn’t it possible that you possess some subconscious concern regarding your daughter’s virginity?”

Ann’s frown cut lines in her face. She didn’t like all this Freudian stuff. Innuendoes were hard to defend against, especially sexual innuendoes. “I can’t see why.”

“Of course you can’t,” Dr. Harold said, still smiling. What did he mean by that? Then he asked, a bit too abruptly for Ann’s liking, “Have you ever had a lesbian experience?”

“Of course not.”

“Have you ever wanted to?”

“No.” I’m getting pissed, she thought. Really pissed, Doc.

“You’re sure?”

Ann blushed. “Yes, I’m sure,” she nearly snapped.

“The dream is rife with overt sexual overtones, that’s the only reason I ask such questions. What is the word you keep hearing in the dream?”

“Dooer,” she said, pronouncing doo-er. “What’s it mean?”

“I don’t know. It’s your dream, isn’t it?”

“Yeah, and what might it, or any of the dream, have to do with lesbianism?” Now the lawyer in her was making an interrogatory that she knew he couldn’t answer.

But he did answer it, by making her answer it. “The voice that spoke the word— dooer—was it male or female?”

“Female. I already told you.”

“And the figures around the birth table, the figures touching you, caressing you, were—”

“All right, yes, they were female.” That’s what I get for trying to play games with a shrink, she thought.

His next observations disturbed her most of all. “It’s interesting that you take such aversion to questions pertaining to lesbianism, or potential lesbianism. It’s interesting, too, that you are now exhibiting a guilt complex about that.”

“I’m not a lesbian,” she said.

“I’m quite sure that you’re not, but you’re afraid that I might think you are.”

“How do you know?”

“I know a lot of things, Ann. I know a lot of things just by looking at you, by assessing the way you structure your replies, by your facial inflections, your body language, and so forth.”

“I think you’re grabbing for shit, Doc.”

“Perhaps, and it certainly wouldn’t be the first time a psychiatrist has been accused as such. What I mean is that no mode of rapport between a doctor and a patient is more important than openness.”

“You think I’m not being completely open with you?”

“No, Ann, I don’t.”

How about if I gave that big mustache of yours a good hard yank? Would that be sufficient proof of openness?

“You’re outwardly rebellious and defensive, which is a sure sign of a deep sensitivity. You haven’t been fully open to me about the dream, have you?”

Of course she hadn’t. But what was she supposed to say?

“Are there any men in the dream, Ann?”

“I think so. At least, there seem to be men in the background, chopping things, chopping wood, I think. They seem to be throwing wood on a fire.”

“Wood. On a fire. But you say the men are in the background?”

“Yes,” she said.

“And the figures in the foreground are women?”

“Yes.”

“And who is the center of attention to these women?”

“Me.”

“You. Naked. Pregnant. On the birth table.”

“Yes.”

“Don’t you find it interesting that the active participants of the dream are women, while men remain in the background, clearly symbolizing a subordinate role?”

“I plead the Fifth,” Ann said. Dr. Harold was boxing her in now, cornering her. It made her feel on guard. Moreover, it made her feel stupid, because she didn’t know what he was driving at. “A minute ago you said you didn’t think I’d been completely open with you about the dream. How so?”

“My conclusions will make you mad.”

“Hey, Doc, I’m already mad. Go ahead. Lawyers don’t like to be accused of withholding information.”

“But they do, don’t they? Isn’t that part of the trade? Withholding facts from the opposition?”

“I’m leaving,” Ann said.

“Don’t leave yet,” Dr. Harold said, lightly laughing. “We’re just beginning to get somewhere.”

Ann stalled. Her head felt like it was ticking.

“First, I’m not the opposition,” Dr. Harold asserted. “Second, I make references that trouble you because being troubled is a demonstration of the very subconscious underpinnings that have recently made you feel unfocused and confused.”

Ann didn’t care about any of that now. She wanted to know what he was going to say. “What? What conclusions? What is it you feel I haven’t told you?”

“You already know.”

Ann’s eyes bore into him. But, again, he was right, wasn’t he? She did already know.

“Tell me,” she said.

“What you haven’t admitted to me is that the dream aroused you. Outwardly, you were repelled, but inwardly, you were stimulated. You were stimulated sexually. Am I right or wrong?”

Stonily, she answered, “You’re right.”

“You were aroused and you had an orgasm. Right or wrong?”

Her throat felt dry. “Right.”

She’d told him neither of these facts, yet he knew them. Somehow she suspected he knew them on her first visit three weeks ago. The man was a walking lie-detector.

“Are you experiencing an orgasmic dysfunction at home, with Martin?”

Now Ann laughed, bitterly. What difference would it make? “Yeah,” she said. “Sex has never been a problem for me. I’ve always been…orgasmic. Until now. Since I’ve been having this nightmare, I haven’t had an orgasm with Martin.”

“But you do have an orgasm in the dream?”

“Yes, every time.”

“You’re afraid that an aspect of your past will ruin your future.”

The words seemed echoed, hovering about her head. Is that what the dream meant? And if so, what aspect of her past?

Dr. Harold went on, “Do you—”

“I don’t want to talk anymore,” Ann said. “I really don’t.”

“Why?”

“I’m upset.”

“There are times when being upset is good.”

“I don’t feel very good right now.”

“You have a lot of fixations, the most paramount of which is a fear of seeming weak to others. You associate being upset with being weak. It’s not, though. In being upset, you’re releasing a part of yourself that you’ve kept hidden. That’s an essential element of effective therapy. The exposure of our fears, the release of what we keep hidden. It helps us see ourselves in such a way that we can understand ourselves. When we don’t understand ourselves, we don’t understand the world, the people around us, what we want and what we have to do—we don’t understand anything.”

I understand that I need a drink, she thought.

“I think that it’s important for you to continue comi

ng here,” he said.

She nodded.

“One more question, then I’ll let you go for today.” Dr. Harold unconsciously stroked his mustache. “What makes you certain that you’re giving birth to Melanie in the dream? You said that you were very ill, and that you remained barely conscious for several weeks after the birth. What makes you—”

“The setting,” she said. “All I see of myself in the dream is my body. It’s almost like a movie, going from cut to cut. I never even really see myself, but I feel things and I see things around me. The cinder block walls and earthen floor—it’s the fruit cellar at my parents’ house.”

“Melanie was born in a fruit cellar?”

“Yes. There’s no hospital in Lockwood, just a resident doctor. I went into labor early, and there was a bad storm, a hurricane warning or something, so they took me down into the fruit cellar where it would be safer.”

“And this strange emblem, the one on the chalice and the larger one on the wall, was there anything in the fruit cellar that reminded you of that?”

“No,” she said. “It’s just a normal fruit cellar. My mother cans and jars her own fruits and vegetables.”

Dr. Harold pushed a pad and pencil across his big desk. “Draw the emblem for me please.”

She felt sapped, and the last thing she wanted to do was draw. Quickly, she outlined the emblem, the warped double circle on the pad.

Dr. Harold didn’t look at it when he took the pad back. “So you’re off—where is it? To Paris?”

Ann smiled genuinely for the first time. “We’re leaving tomorrow. I’ve just got a few things to wrap up at the office this afternoon, then I’m picking up the tickets. Melanie’s an art enthusiast, she’s always wanted to see the Louvre. It’ll be the first time the three of us have been away together in years.”

“I think it’s important for you to be with Martin and Melanie on a leisure basis. It’ll give you a chance to get reacquainted with yourself.”

“Maybe the dream will go away for a while,” she said, almost wistfully.

“Perhaps, but even if it doesn’t, don’t dwell on it. And we’ll talk about how you feel when you get back.”

In the Year of Our Lord 2202

In the Year of Our Lord 2202 The Minotauress

The Minotauress Terra Insanus

Terra Insanus The Stickmen

The Stickmen Flesh Gothic by Edward Lee

Flesh Gothic by Edward Lee Family Tradition

Family Tradition You Are My Everything

You Are My Everything The Backwoods

The Backwoods The Teratologist

The Teratologist Smoke and Pickles

Smoke and Pickles Buttermilk Graffiti

Buttermilk Graffiti Dahmer's Not Dead

Dahmer's Not Dead Quest for Sex, Truth & Reality

Quest for Sex, Truth & Reality The Innswich Horror

The Innswich Horror Brides Of The Impaler

Brides Of The Impaler Goon

Goon Trolley No. 1852

Trolley No. 1852 Sacrifice

Sacrifice Monster Lake

Monster Lake Succubi

Succubi Lucifer's Lottery

Lucifer's Lottery Monstrosity

Monstrosity The House

The House The Dunwich Romance

The Dunwich Romance Operator B

Operator B Bullet Through Your Face (improved format)

Bullet Through Your Face (improved format) Grimoire Diabolique

Grimoire Diabolique Room 415

Room 415 The Messenger (2011 reformat)

The Messenger (2011 reformat) Incubi

Incubi The Black Train

The Black Train House Infernal by Edward Lee

House Infernal by Edward Lee City Infernal

City Infernal Creekers

Creekers The Haunter Of The Threshold

The Haunter Of The Threshold Mangled Meat

Mangled Meat The Doll House

The Doll House Header 2

Header 2 Bullet Through Your Face (reformatted)

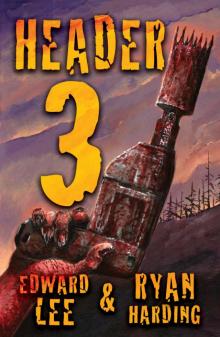

Bullet Through Your Face (reformatted) Header 3

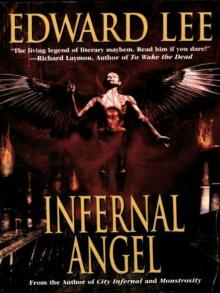

Header 3 Infernal Angel

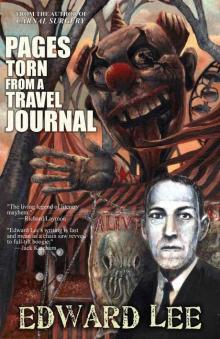

Infernal Angel Pages Torn From a Travel Journal

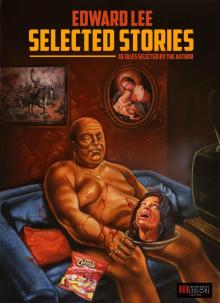

Pages Torn From a Travel Journal Edward Lee: Selected Stories

Edward Lee: Selected Stories The Bighead

The Bighead The Chosen

The Chosen